Open Source Business Metrics Guide: How to Build, Grow, and Measure the Success of an Open Source Business

Open source has become one of the most recognized movements in technology in the last decade. Already 90% of IT leaders use enterprise open source software, and by 2026, the open source services market will be worth $50 billion. Based on the growth It is not surprising that the number of open source projects and businesses based around open source have skyrocketed over the past decade. While open source itself is not a business model, we can clearly identify business models built around open source licensing and philosophies that have proven sustainable, scalable, and profitable. To build an open source business, it is imperative to grow not only the business and the adoption of your software but the community around it. In this guide, we walk you through those challenges and key metrics that you'll want to track in order to get your open source business off the ground and keep it up and running.

Selling open source is very different from classic business models

For years, people have built successful businesses on the idea of exclusivity and differentiation. If you are the sole exclusive manufacturer or distributor of a product, you control the destiny of your product. Consider the automobile industry, for example. Ford builds cars. If you want to buy a Ford, you go to a Ford dealership. Ford uses its channel of dealers to offer you their product. Ford tries to build better cars than its competition, offering distinction exclusive to their brand or their umbrella organizations. They may license the technology to other automotive companies, but Ford controls their technology, the channels for sale, and ultimately holds more control over end-to-end business. Whether you are a car manufacturer or software company selling enterprise software, success is often predicated on having a better, more popular, or some differentiated product.

In the open source industry, your own product is your greatest competition. Users can download software for free without any commitment or even acknowledgment that they are using it. You must be able to differentiate your paid-for offering enough for users to choose it over the free version. Referencing our previous car example, it's as if you could lawfully walk up to a lot, get into a car, and take it home without paying anything or telling anyone you were taking the car. That is how most open source projects operate. A person (group or company) builds software and puts it on the web (or on GitHub) for users to download, use, and modify for free.

Building a customer base from the growing adoption of free users

Although giving away a product may seem counterintuitive from a business perspective, it serves as an effective top-of-funnel strategy for building a loyal, passionate customer base.

Let's go back to the automotive example. The automotive industry makes money from selling a physical good: your car. Building that physical car involves a built-in cost for each unit sold, which needs to be recouped. In this case, building 1 million cars requires a higher manufacturing cost than building 100,000. In the case of software, building a product used by 1 million people is no more or less costly than building software used by 100,000, support costs (or infrastructure for SaaS companies) aside. In other words, the cost of software for 1 million users remains the same as the cost for 100,000, allowing you the freedom and flexibility to explore different models for monetization. For instance, you can establish ways to increase sales among existing users.

You may have heard that acquiring a new customer can be 5x more expensive than selling to your existing customer. Existing users already know your product, they have developed some loyalty to it, and they have a vested interest in contributing to improve the product upon which they rely.

The question comes down to how to convert free users to paying customers, but the answer may appear more straightforward than you realize: Offer a product that is valuable enough to pay for. If your software provides enough enhanced value over the free version, a subset of users will pay for it. This is similar to the freemium strategy deployed in the mobile industry. For example, if 10% of your user base will pay for your enhanced-value software, and you grow your user base from 100,000 to 1 million people (10% of 1 million is more than 10% of 100,000), then you position yourself for commercial opportunity. It's a strategy that existed well before the open source movement in the form of free trials and basic free services.

To be successful with this approach:

- Know what your users are willing to pay for

- Be able to adjust your product to stay ahead of needs and ahead of the community potentially implementing features

- Maintain a steady growth rate of users trying, deploying, and running your software

- Improve your conversion rates from free users to paid users

Common open source business models

In the open source space, the upsell can take a few forms. Let's walk through the most common ones.

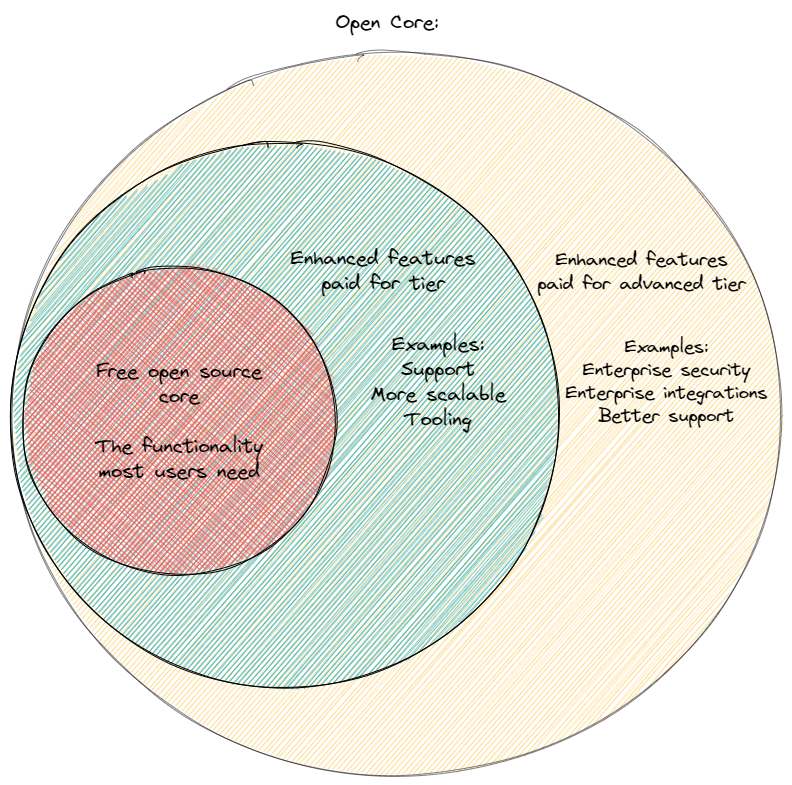

Open core

Open core is the most classic open source commercialization strategy. It consists of giving away a basic or foundational product for free and only asking people to pay for a more enhanced version of the open source product. This version is typically called the enterprise version and enables greater efficiency as well as additional, more robust features. To illustrate, imagine giving away free cars, but the gas tank of these free cars can only fill up to two gallons at a time. In contrast, if someone pays the full price for the car, that individual can get a full 20 gallons and increase the range from 50 miles on one tank to 500 miles. The open core model operates similarly.

Many companies have started with an open core model. Within this model, the primary differentiator consists of enterprise features, such as encryption, security, and scalability. Larger companies with deeper pockets are more likely to buy a software license and support contract. Another popular open core tactic is to make the server software fully open source but the tooling for easily operating, developing against, or managing it as part of a paid- offering.”

Risk of competition from the community presents the biggest challenge with open core. Other companies in the space as well as contributors, will often provide viable alternatives to your enterprise components. In the last five years, we have seen more and more users who feel that open source versions are good enough and refuse to pay for the tooling or features that open core versions offer. They prioritize easy-to-use over high-end features. Consequently, more and more people view the cloud as a better investment.

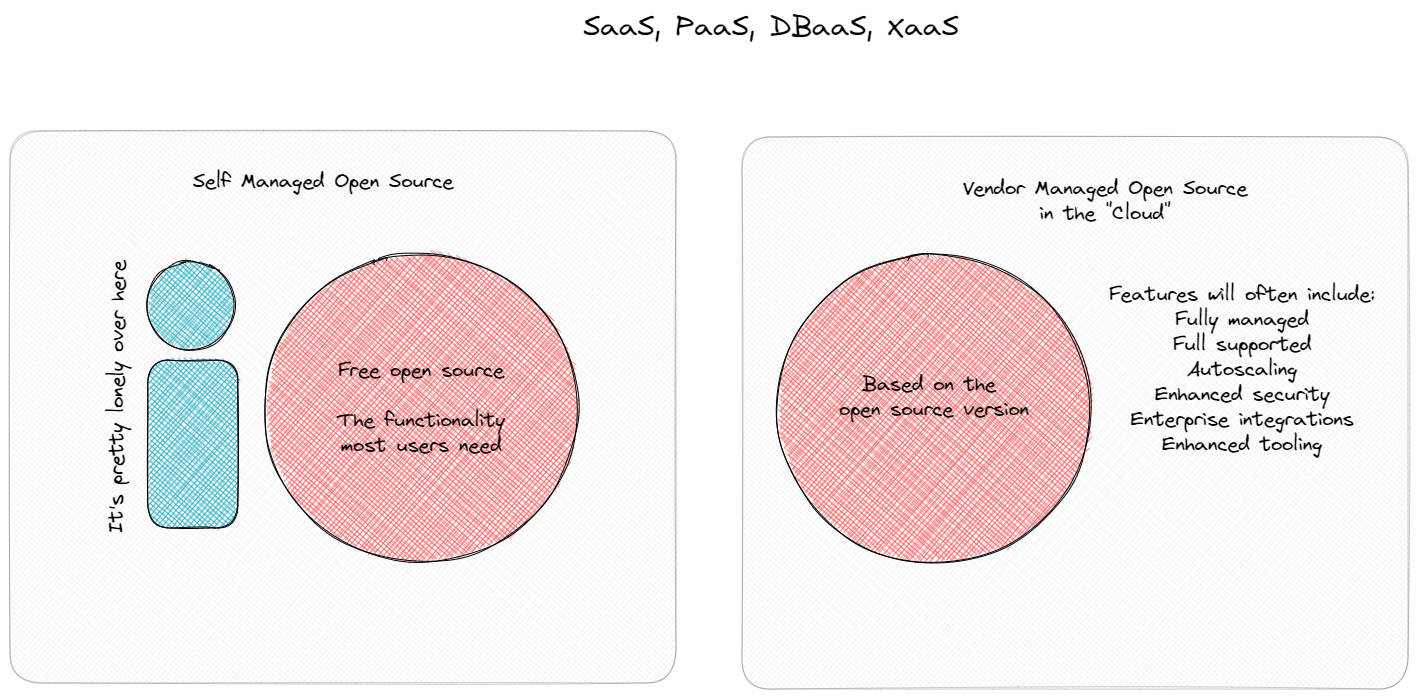

SaaS/PaaS/XaaS

Over the last five years, X as a service has become the most popular model. It seems that almost all open source companies now run or try to build a cloud or an as a service offering. In this model, you allow people to run the software as open source on their own but then offer a managed cloud offering so that they don't have to manage it for themselves. This is often paired with features exclusive to the cloud space. Going back to the automotive example, it's like an automotive lease. You don't own the car—you lease it. The dealer takes care of most of the maintenance and you can use the car as long as you pay. If you drive more miles than the lease allows, then you pay more.

Many open source companies choose this model comes because it provides a higher degree of stickiness or lock-in. They rely on you not only to provide the software but also operate it and make sure it stays running, safe, and updated. In addition, you gain a lot more information on how your users are using your product, which can be used to enhance, improve, and expand your software and offering. Finally, usage data and workload patterns can help identify expansion opportunities as well as stave off churn.

The biggest challenge in the cloud space is that the market is already crowded. Although not all open source software lends itself to a cloud offering, the most widely used infrastructure tools already have versions or similar tools available in most major cloud providers. As a result, you must convince users that your offering provides greater value over the more integrated cloud provider stacks. Users looking for the easy route will choose the path of least resistance.

Support and services

Another classic open source business model is offering support or services. In this model, you anticipate that a percentage of your users will need dedicated help running, setting up, or troubleshooting the software. Going back to our automotive example, this is like an extended warranty plan or a maintenance contract that includes regular oil changes, maintenance, and emergency repairs.

Large enterprises still value a support contract and will often pay a premium for it. Despite the fact that a significant number run their own internal cloud and don't rely on a public cloud, companies are increasingly opting for a managed service or cloud offering that includes support and operational management. For open source businesses, providing services is the easiest starting point for driving revenue.

The biggest barrier with a service-based model is proving your value. Otherwise, customers will not renew their contracts. If a customer pays for insurance but never uses it, the customer will constantly question the value of that expense. This is especially true in the open source space where customers could turn to the community for free support in a time of need. Furthermore, the margin for services is generally very low and not attractive to investors.

The open source funnel

The success of all these models relies on driving people from a free to paid relationship, a journey outlined by the open source funnel.

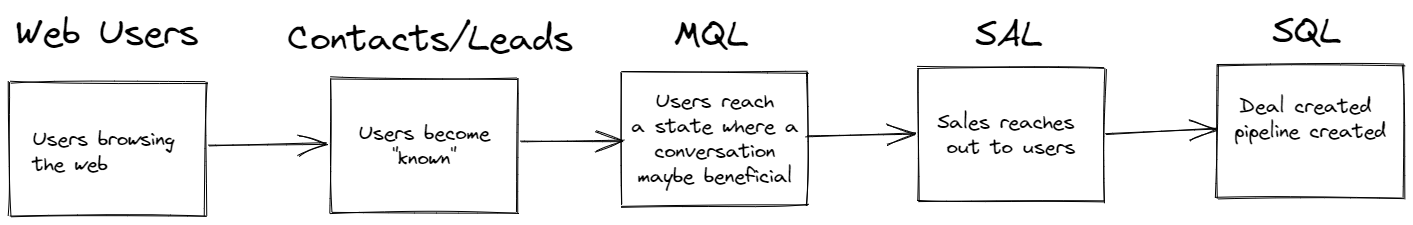

The open source funnel differs from the classic marketing funnel, which looks something like this:

With the marketing funnel, you want to generate inquiries and grow your digital traffic and engagement so that eventually, those who interact with your site become a lead or contact. After a specific number or set of events, whether it is clicking on a webpage, registering for a webinar, opening up an email, or watching a video, the lead eventually qualifies as a marketing qualified lead (MQL). The MQL becomes a sales accepted lead (SAL) once the lead is ready for the sales team's follow-up and thereafter turns into a sales qualified lead (SQL) once the lead has advanced through the sales pipeline. SQLs will likely become customers and either become lost deals or closed won deals.

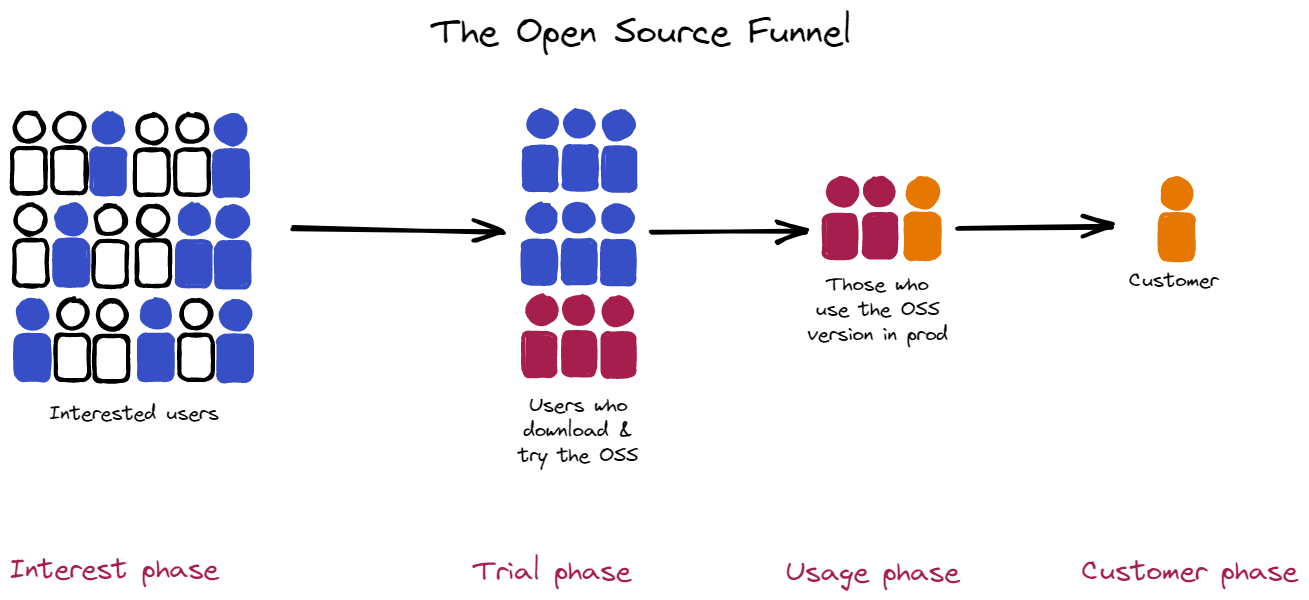

In contrast, the open source funnel looks something like this:

With more interest comes more downloads, and with more downloads comes more production deployments as well as more users who are willing to pay for something of value. Naturally, dropoff will occur at each stage. Nonetheless, open source provides the advantage of a larger-than-normal pool in the initial interest phase, which can very nicely set up the rest of the funnel for maximal conversion.

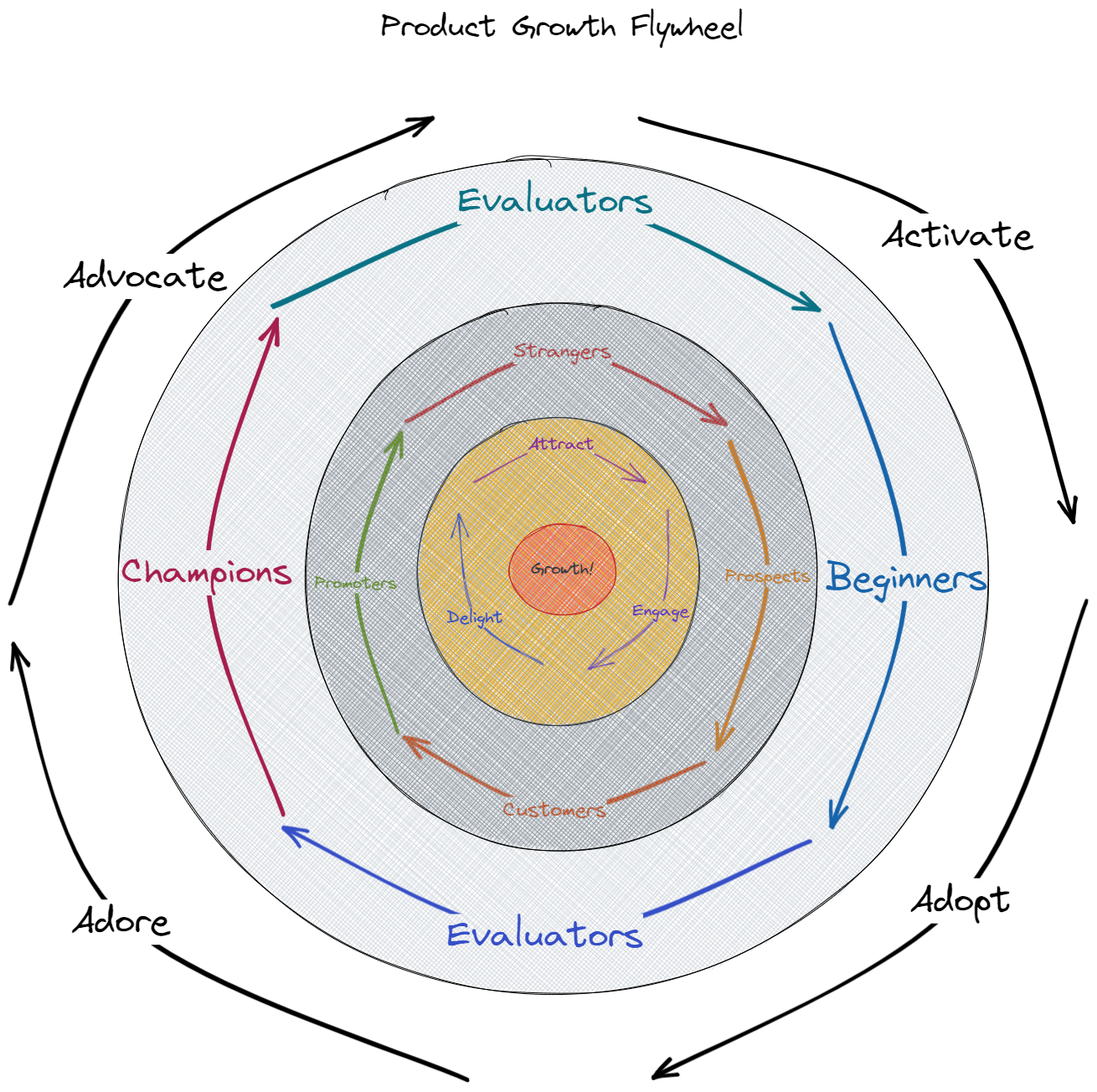

In companies focused on product-led growth, you may be more familiar with using the growth flywheel:

In this setup, evaluators are those reviewing your project and downloading it. Beginners are those using it in production. Regulars are those willing to pay. Champions are fans of you and the open source project.

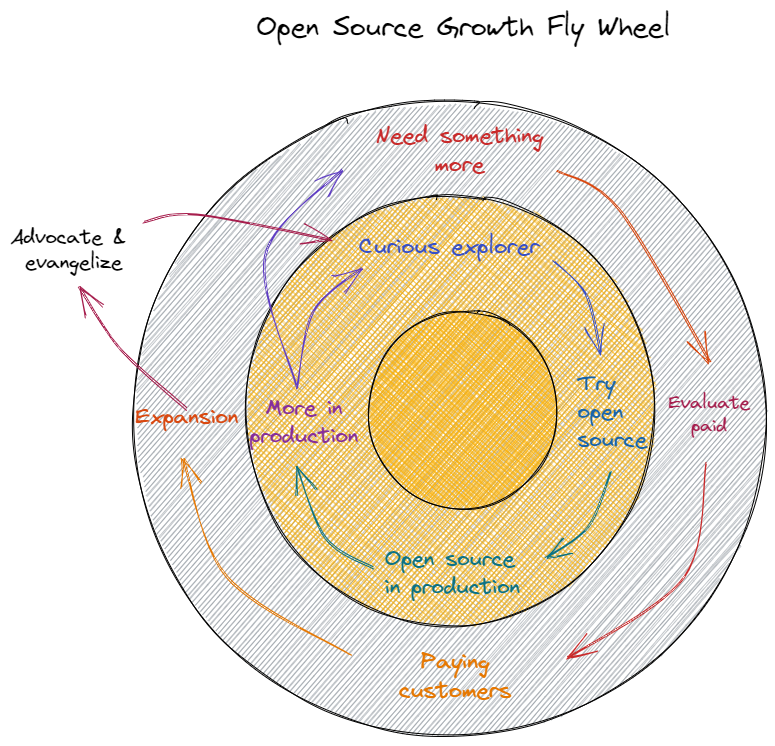

The flywheel can also be applied to open source companies, as represented below:

You still attract people to your open source project, engage with them, and generate interest, but that interest causes them to try your open source project first for a non-production workload (e.g., a small trial application or just trying to build something on a laptop ). The goal is to make that experimental experience so exceptional that it makes them want to move a production workload to the software or build new applications with the software. The more comfort a user gains with the project, the more applications that they will want to deploy and the more they will want to use your software in production. Note: It may prove easier to create advocates and evangelists from your free users than it may be to create paying customers.

At this point, two goals emerge: First, you want them to share their experiences with others to propel further interest in the project and help you grow your potential user base. Second, once they rely on your software for mission-critical applications, you want them to recognize the value of and experiment with your enterprise offering. In this way, they enter into a similar cycle of trying the software or service and eventually moving into production.

Whether you're looking at the flywheel or open source funnel, more users trying your open source software is always better. This is why many companies prioritize acquiring the largest open source install base possible first and foremost. With millions of users, you can eventually image out how to monetize the user base even if your customer base is relatively small now. In fact, this philosophy of growth at all costs has dominated much of the industry over the last five years.

Since the beginning of 2022, the shift in economic climate has caused companies to reevaluate their plans. Efficiency and a faster path toward profitability have replaced the growth-at-all-costs mentality, leading to more emphasis on conversion rates and customer acquisition costs (CAC). The switch from gaining more users to growing the right users has made messaging, positioning, and targeting specific personas vital for growth.

Efficiency, renewal, expansion, and growth

Gaining massive year-over-year growth for your open source project is easier starting out than after you have an established project. It is not uncommon to see projects and companies grow 4–5x year over year. As a project reaches market saturation, growth gradually tapers off and the focus turns to feature set and functionality expansion so that you can jump into new markets (for instance, a NoSQL database focused on documents adding transactional and relational workloads.

As the company matures, you want to expand the usage of existing customers and leverage the hard work of having already acquired them. In fact, many larger organizations plan for 125% net retention from their customer base (simply check out the annual or quarterly earnings reports from some of your favorite open source companies). Effectively, these companies expect $1.00 of revenue from customers this year to deliver $1.25 next year. They achieve this only by reducing churn and expanding the usage of products within existing customers. Regardless of your business model, continued success requires you to build natural pathways for expansion.

The importance of growth for commercial success

An increasing number of open source projects are becoming commercially viable. Companies looking to scale these projects must rely on growth metrics for a variety of reasons. First, investors seek indicators that projects will deliver a good return on their investment. A growing user base indicates a growing potential customer base. Second, understanding the potential customer pool is vital to understanding how to build and structure your business. With growth comes new opportunities to expand the project, enhance the feature set, and pull in more contributors, users, and eventually customers, who augment the use cases of your project, bring fresh ideas, and provide vital feedback. Finally, the right set of growth metrics also provides insight into what is not working and what adjustments need to be made.

The challenge of tracking adoption and usage

When we talk about growing an open source project, we often refer to growing its adoption and usage. A burgeoning user base yields a cascading impact on the rest of the project, often leading to more contributors, more community engagement, more funding opportunities, more potential sales, and more downstream effects. Tracking adoption, however, in the open source space is difficult. Ideally, you would be able to count the actual number of people using your software, but in reality, that is not an option—users value their privacy, downloads come from third-party repositories, people build from source code, and software with baked-in telemetry is commonly frowned upon. In an effort to try and understand the adoption cycle, you are usually left examining a series of metrics that reflect and indicate interest, awareness, adoption, and contributions but that don't fully match true usage.

Why can't you track running instances?

Tracking running instances requires telemetry built into your software that calls home and sends some data packets back. Although a number of users are willing to provide this level of data, many are concerned over how the level of tracking and overall implementation of such a system affects their privacy. The open source companies that have implemented built-in telemetry (or at least tried to) have experienced varying degrees of success, including community backlash, which in some cases have diminished the user base.

In fact our experience is that even when the data collected by two different entities are entirely identical, people are sensitive to how the data is collected. Scarf saw that end users were actually more comfortable with completely silent pixel tracking than they were with phone home mechanisms in NPM packages (despite it being a subset of what NPM was already collecting).

This begs the question of how you would not only come to understand who is using your software but also how they are using it three, six, to 12 months after installation and even continuously, if possible, without compromising trust.

What about the cloud?

The cloud to some degree can provide a way around this. When people sign up for a cloud-based service they provide their information and grant you authorization both to run the software for them and access more granular metrics on their usage. As a result, you can gain a detailed understanding of their needs. That said, most open source software falls outside of the cloud space. Most cloud providers who provide open source as a service offer the commercialized version of what is already downloadable and installable without a commercial agreement. Still, a large portion of the user base exists that will try out the open source software on their own either via downloaded packages, containers, or building from source. What about getting adoption and usage details for those users?

Measuring success

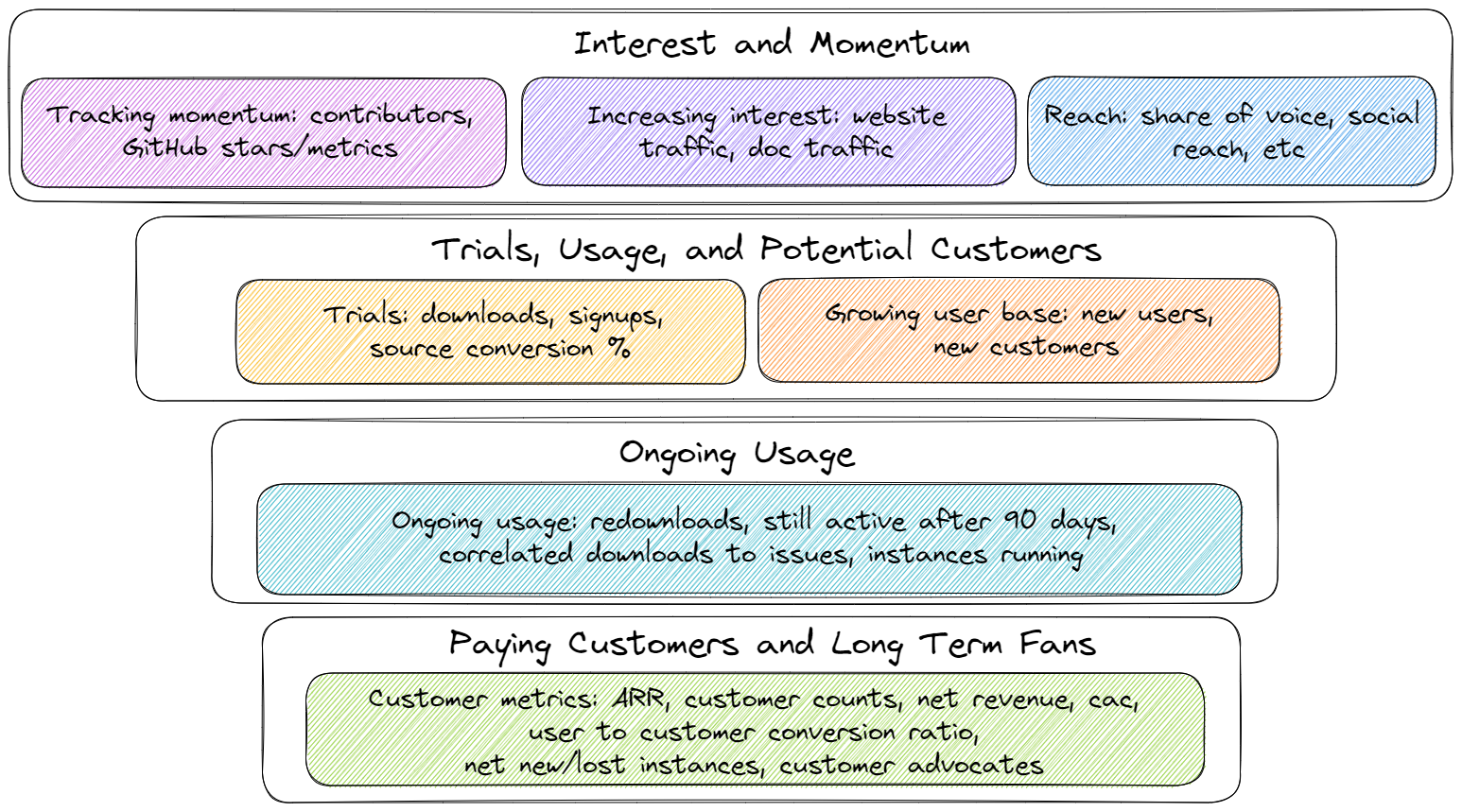

Top of the open source funnel: How do you track interest?

Isn't open source largely tracked via contributor usage? Should GitHub-esque metrics remain the de facto standard for project health, adoption, and growth? The answer to both questions is no. Contributor metrics are great, but they don't predict the commercial success of a product. Having more contributors than other similar projects may look good on paper, but that doesn't denote users. Similarly, an increase in the number of contributors, pull requests, or issues on GitHub does not mean your project's user base is growing. It could even indicate the opposite. Growing the contributor base is certainly a directionally helpful indicator of a project's health and adoption, but it does not always directly correlate, nor is it a comprehensive measure considering all the other factors to take into account. So, what metrics should you look at to understand the overall growth of your project?

Contributors (code or evangelist)

Tracking contributors still matters, but the way in which you do it makes a difference. Several projects have a handful of large corporate entities that contribute heavily to the code base of a project. You'll see spikes in contributors over time when in reality, those indicate when a new company joined the ecosystem. Tracking the companies, as well as the individuals who contribute, can help mitigate this. If a company or individual cares enough about the project to contribute to it, you are seeing growth. You can track such metrics in GitHub/GitLab, Bitergia, or in a tool like Orbit or Common Room that aggregates multiple sources.

The caveat is that measuring the overall growth of all advocates, not just the code contributors, is difficult. Besides examining the number of people contributing to the code, you also want to look at the number of people releasing videos, blogs, talks, and other content into your ecosystem. These soft contributions can show project growth and success even better than hardcore code metrics, but tracking them is often manual.

Tracking the number of GitHub or GitLab stars

Another important top-of-funnel metric is project traffic and activity on sites like GitHub or GitLab, which offer more meaningful data over a metric like GitHub stars. In principle, more stars on GitHub would seem to equate to more interest or growth, but there is cause to think twice. A cursory search shows that dozens of services will give hundreds or thousands of stars to your project for only a few dollars. Some projects hold a suspiciously large number of stars for the code available.

Rather, project traffic and activity as reflected by the number of issues, merges, commits, etc., on GitHub, prove more telling. Moreover, it is more important to evaluate the number of unique users performing those activities over the raw number of activities. Unique traffic to your repositories, the unique number of forks, and the unique number of clones of your repo are all worth tracking in order to gauge growth.

Website traffic and digital presence

We've covered some key metrics for measuring interest that come from external sources. Let's take a closer look at some of the internal sources of data within your company that you can review. To access these numbers, you can employ a service such as Google Analytics, Chartbeat, Semrush, Amplitude Analytics, or Pendo, and work with your web development team to gain access.

Unique views

Because bots and crawlers on the web can cause peaks in website traffic, identifying the number of unique views or companies interacting with your site is more valuable than the number of raw page views. You should be able to track the trend of your traffic over time and explain the dips and spikes. Growth of uniques over time shows increasing interest in your product.

>> read more about traffic metrics

Engagement with documentation, tutorials, and guides

Another indicator of interest in your product lies in a subset of your website traffic: engagement with docs, tutorials, and guides. Increased traffic of unique visitors in these sections typically signals more people who are seriously interested in trying out your product. It is also important to note that there are different weights to people's actions that you should take into account, for instance, someone who revisits your website over and over again or someone who reviews your pricing page indicates more interest than merely a one-time visit to the homepage.

Referrals

Bear in mind that metrics do not merely revolve around the absolute numbers. It is also important to know where the numbers come from to evaluate reach and awareness. You want to know what external sites or platforms served as the channel by which someone landed on your website. This requires an understanding of who is linking to your content, what other websites mention your product, and what other websites reshare your content.

Share of voice

Share of voice attempts to measure your share of a market and overall awareness. When people search for, talk about, or suggest tools in this space, how often are you in that conversation? How do you rank in search engine optimization (SEO)? How many mentions do you get versus your competition? Are you receiving external press and coverage? A lot of companies spend an enormous amount of time, money, and effort chasing mindshare only to find that they did not get the outcome that they expected. Due to the nebulous and complicated nature of calculating share of voice, we recommend waiting until later on in a project lifecycle to attempt to measure this.

Social reach

Your social reach centers less around an individual metric and more around a series of metrics aggregated to give an overall picture of growth among your followers. Typically, we seek growth in the following:

- Number of followers

- The number of likes/shares

- Engagement: How many people have been part of a discussion on social media?

Middle of the open source funnel: How do you track usage?

Once a user shows interest, the next step is to encourage a download, grabbing of a Docker container, or grabbing of the source code itself to experiment with. This is the first time when your product can speak for itself. For a project maintainer or owner, this is also the first concrete step for increasing project adoption.

The disadvantage in this phase is the difficulty of collecting data because the default tends to be anonymity. In many cases, it is challenging to collect and measure the data without a third-party tool or service.

Nevertheless, there are ways to work with what you have. You can review the metrics outlined below to get a sense of how usage of your product is trending.

>> read more about adoption metrics

Raw downloads

The total raw number of downloads can indicate how your project is growing but should always be taken with a pinch of salt. The risks include redownloads, whether by bots or by real users, which can skew numbers and be misleading if looked at in isolation.

Scrubbed unique downloads

Scrubbed unique downloads are a slight modification on raw downloads and aim to identify the real number of downloads by looking at how many unique companies or users have downloaded your software.

Enhanced download metrics with metadata

Identifying the unique person downloading and using your software is challenging with open source, but fortunately there are tools and methods available that can at least provide enriched metadata about your users, including location, company, other pages that they may have accessed on the website, and the like. You can pull this information from the logs or employ a tool like Scarf.

Net new users/companies

This one is quite straightforward. It is essential to understand how many new people are trying your software.

Signups

If you have a SaaS offering and a free tier, you'll automatically have a concrete metric for knowing how many people are experimenting with your product because it will require a signup to get started. What is more, users will likely tell you who they are during the onboarding process because of the information that you ask them to enter when signing up.

Once you have a solid understanding of how your product is used, the next step is to analyze behavior that precedes conversion.

Page, docs, or source-to-download conversion ratios

You should know what leads a user to download. Understanding which content, pages, docs, or other sources or channels users visit before deciding to download helps you optimize and increase those numbers because you get a better sense of what your target audience seeks.

Docs views from those who have already downloaded

We've talked above about the need to track documentation and website traffic, but it is also important to track views from those who have already downloaded your software or packages. Some users may only download once and often deploy from that single download. This means that the actual deployments or usage of your software may be hidden behind a single download number. Tracking downloads and continued engagement on the website and from docs will reveal continued usage.

Bottom of the open source funnel: Who is using your product, and more importantly, who is willing to pay?

Redownloads or multiple downloads over time

The same users downloading your software over and over again shows ongoing usage and possible growth of the number of installs. This number and rate of downloads can also help determine changes to deployments or the overall install base that may occur.

Users still active 90 days after their first install

The best predictor for potential production usage or a possible future customer is ongoing usage. You want users to still actively use the software 90 days after downloading and installing it, and to do so after 180 days is even better. If the number of users who drop off before 90 days is high, then either the value of the software may be too low or the barrier of entry may be too high. To track active instances or uses of the software, you can use some lightweight telemetry or in the absence of that, repeated downloads.

Companies and organizations using the software for more than six months

Whereas the above metric focuses on users, this metric focuses on the total number of users at a single company or organization. Multiple users at the same company might be downloading and using the software. If you know that multiple users from the same company use your product repeatedly, that is a powerful indicator of potential growth.

Company downloads accompanied by GitHub repo activity and issues

Another powerful indicator of potential customers is the number of those who download your product and then open issues in GitHub or commit code to your repositories.

Call home telemetry: Instances/installs running at a company

The best way to track growth is to understand how many companies and users actively use your software and whether they are increasing or decreasing the number of active deployments. You want to know the number of active instances, the number of new instances running in the last X days, the number of churned instances, etc.

Customers, users, and retention

Every company tracks a set of business metrics that they review on a regular basis, which may include metrics such as annual or monthly recurring revenue (ARR or MRR), the number of customers, and net revenue. Open source specific metrics complement these standard business ones. A thriving open source business will focus on both, together with the acquisition of net new customers and retention of existing customers. Consider taking a closer look at these as you seek to evaluate the bottom of your open source funnel.

>> read more about customer metrics

User-to-customer ratio

The ratio of users to paying customers is one of the top five metrics that you should track and constantly look to improve. You can acquire customers by increasing the overall number of users and improving the conversion rate. Early on, you may find it easier to increase the overall users by orders of magnitude, but as the market changes, the growth rate slows down as you capture more and more of the available market. This is why converting users to customers is critical.

Instance and user churn

Once you know the number of instances of your software running in unique organizations, you can identify dwindling counts of installed or running instances, which can foreshadow the potential churn of a customer. Decreases in the number of users or instances may indicate issues within the software or losses to competition.

Customer advocates

Earlier we highlighted the significance of tracking contributors (whether it's code contributions or evangelism), but it is also important to segment out and track paying customers. Paying customers who are active in your community are a valuable source of feedback and help instill confidence in potential users and customers.

Open source competitive analysis

Check if your key users and customers are contributing to your competitive open source products. Their behavior will serve as a useful predictor of potential churn.

>> read more about predictive churn metrics

Conclusion

Not every department or team will value all of the above metrics the same, but these metrics as a whole do track the various stages of the user and customer lifecycle. Based on these metrics, you can gauge the overall interest in an open source project and determine if your decisions result in further adoption. Marketing and sales can ensure a growing funnel and close more deals. VC firms can evaluate business performance and receive assurance that their investments produce promising ROI. What is more, you can use the insights to improve your product and better satisfy the needs of your target audience.

Even though open source has existed for a while, the playbook for open source done right is still in the making and ever evolving. Despite three major models repeatedly emerging in the space, there truly is no traditional path for the open source business. Yet the need to account for growth, as with any company, still applies.

Measuring the interest, adoption, and growth of open source projects extends beyond just contributors. It is important to triangulate key metrics within each stage of the open source funnel to draw meaningful analysis and conclusions that can help you understand how users are progressing through the customer journey. One of the many beauties of open source is that it provides a broad user base by opening up the technology to anyone and everyone who takes interest thanks to virtually no financial barrier to entry, or any barrier at all! To that end, if you can appeal to loyal existing users and find a way to both monetize and augment their usage, the possibilities could be exceedingly beneficial and worth billions of dollars. Open source creators plus data-driven insights make for a powerful combination.

Understandably, setting up the metrics essential to achieving this can feel cumbersome and time consuming. If you are serious about sustaining the growth of your open source business and want help with measuring the metrics discussed in this paper and more, you can check out Scarf and learn about package SDKs, Scarf Gateway, documentation insights, and open source support. The tools created by Scarf make it easy to track downloads as well as gain visibility into the user lifecycle.

Get started with Scarf today or feel free to contact us if you have any questions.